story

Celebrating the Art of L. Frank

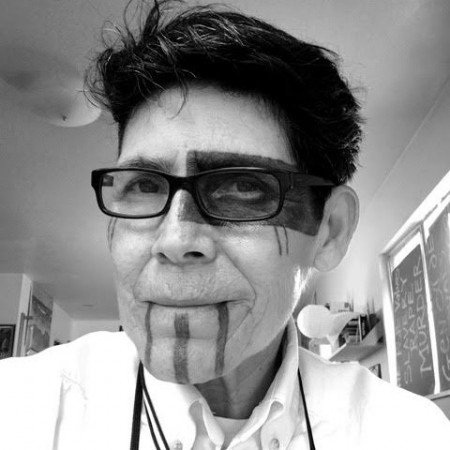

For L. Frank Manriquez, who is a Two-Spirit person of Tongva, Ajachmem, and Rarámuri descent, her art is an expression of the invisibility of her culture. As an active decolonizationist, culture keeper, and artist, she co-founded the Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival to combat erasure and previously served on the board of the California Indian Basket Weavers Association and the Cultural Conservancy.

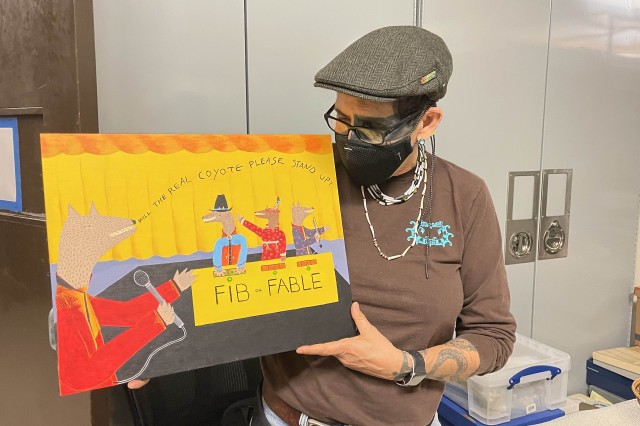

Her art has been featured worldwide in museums and art galleries– and locally in 2021 as part of Cara Romero’s Tongvaland campaign. In 2009, the Museum accessioned a painting entitled Fib or Fable by L. Frank. We sat down with L. Frank to hear about her art and how it speaks to communities that are typically erased from mainstream L.A. culture.

I figure that the only way people can really believe anyone else is through actions. I can talk, talk, and talk, but what have I done for our people lately? I don’t feel that because I did something that was difficult or scary (and it was for our people) that I can rest on that, you know? What have I done lately, what have I done for the next seven generations?

L. Frank Manriquez

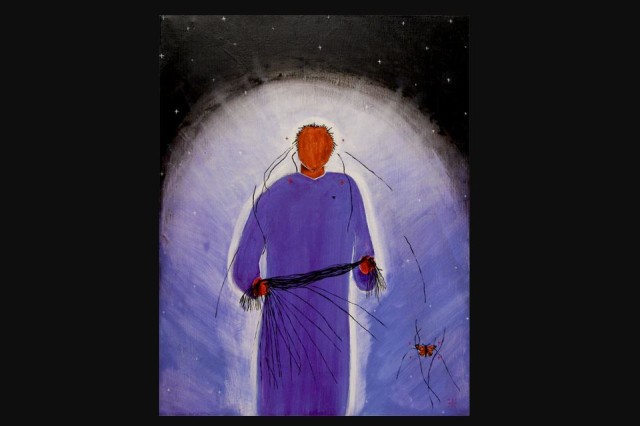

It depends on the medium– If I make something out of stone, I will use different words than if I do an etching. My art is a way of keeping us from invisibility, and by us, I mean our tribes. My art is my voice trying to make sense of things that were long ago– but I feel them very much alive today. Because my people were considered extinct, and everything was taken or bought, we do not have a lot of symbology– so I rely a lot on how I feel about my culture.

But my art’s function is to address invisibility and a way to start a conversation– that is why I use so many different mediums. And the problems you run into when using different mediums are exactly the same, where you are using welding or painting. I like the problems you encounter because that is where you grow [as an artist]. I also like using different mediums because not everyone likes painting, some like stone carvings or cast metals. The goal is to catch the attention of people.

I’ve been taking photographs consistently since I was nine years old. But I don't know if that's my favorite– it's just how I live and breathe. I used to take so many photos that I used to think that when I blinked, I took a photo. You'd think it's my favorite because it's the thing that I’ve never left alone, but I also really like putting metal plates into acid– I think that's pretty bitchin’! I also really love silkscreening, which is why I went to Immaculate Heart College to learn silk screening. But then I also really like animation, and I'm trying to teach myself that, but the software is complicated– so no, I don't have a favorite.

Courtesy of the art of L. Frank

Courtesy of L. Frank

Courtesy of the art of L. Frank

Courtesy of the art of L. Frank

1 of 1

Courtesy of the art of L. Frank

Courtesy of L. Frank

Courtesy of the art of L. Frank

Courtesy of the art of L. Frank

While my renderings and drawings have a lot of life to them (which surprises me), I find them the most challenging. I learned a lot from when I drew my first nude model– I was late for class and came running into class to find this woman posing for us in drawing class who had to be at least 120 years old. So I sat and drew and drew– it was really kinda magical, but what I did in two hours others can do in five to ten minutes! So I find that very challenging. In that same class, my instructor sat down to draw with me, and we figured out it was my dyslexia– my brain was telling me different things than what was actually there. [When I sit down to draw], I’m not really sure what direction I’m seeing things go in, which is why it was so challenging.

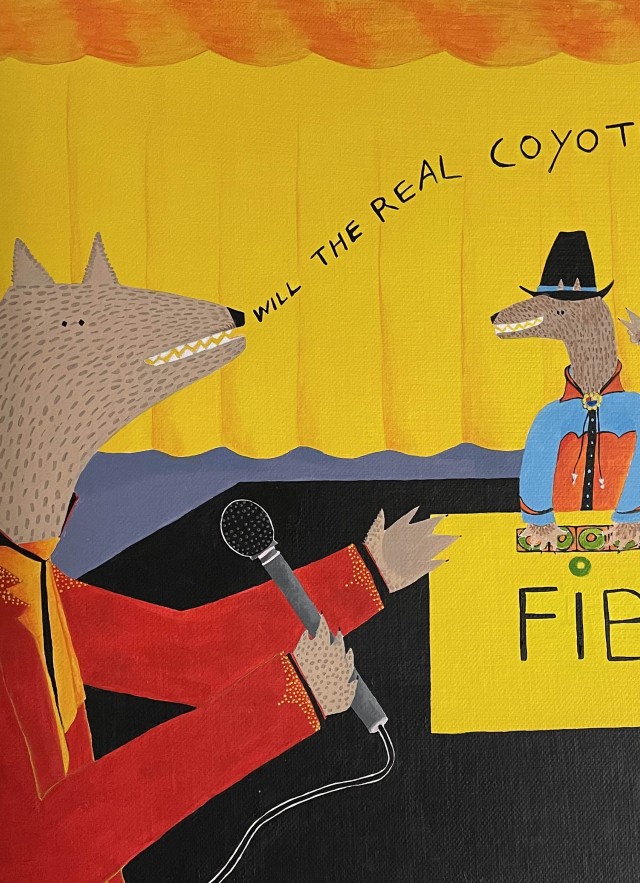

Mostly because I’m a “Hollywood Indian,” all of my references have to do with the screen– the big screen, little screen. Being 69 years old, I remember our family's black-and-white television, which was the kind when you turned it on; there was an Indian in the center with a test grid that radiated out from it. There were few programs back then, but the To Tell the Truth game show would have women in pearls and dresses, guys in suits, and it was always the same– you had to guess who they were, some would lie, and then they would say, “Will the REAL Bob Jones stand up?” Well, those lies struck me as very Coyote-ish since he is often known for lying. So Fib or Fable is about lying, it's about Hollywood, and it's about human beings as complex things.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

L. Frank visited NHM in 2021 and reconnected with her artwork currently cared for and stored in the Museum's Anthropology (Ethnology) collection.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

While visiting the Museum, L. Frank met with Archaeology Collection Manager Chris Coleman, to view a variety of stonework and objects cared for by Museum staff. Here, they are discussing a hopper mortar basket collected during the Channel Islands Biological Survey 1939-1941. (A.4616.39-146)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

L. Frank photographed a variety of objects during her visit to the Anthropology collections, including this mortar from the Charles Prudhomme collection which is one of the founding collections of NHM. (A.4811.40-991)

1 of 1

L. Frank visited NHM in 2021 and reconnected with her artwork currently cared for and stored in the Museum's Anthropology (Ethnology) collection.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

While visiting the Museum, L. Frank met with Archaeology Collection Manager Chris Coleman, to view a variety of stonework and objects cared for by Museum staff. Here, they are discussing a hopper mortar basket collected during the Channel Islands Biological Survey 1939-1941. (A.4616.39-146)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

L. Frank photographed a variety of objects during her visit to the Anthropology collections, including this mortar from the Charles Prudhomme collection which is one of the founding collections of NHM. (A.4811.40-991)

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

So Coyote often does things in the wrong way or teaches us how to do things in the right way by doing it the wrong way– but sometimes Coyote’s just a jerk, and you see that in that painting. The guy on the end on the far right he’s mimicking the announcer. The Native in the center, who is just a Native joker, he's putting the rabbit ears behind the other Native who is just covering up his scores. Coyote is just kind of jerky, kind of silly, and the whole set is the stage.

When I was very little, I used to ride my bicycle or run around some of the movie studio lots because they were near where I lived. I also just watched a lot of movies, and they always had a big curtain and footlights– so quite often in my paintings, there are footlights or theater settings– and here it's the game show.

Well, Coyote’s one of the most prolific teachers we have, and so when I started painting, he just popped out. I think it was also because I was looking at Harry Fonseca’s work, another California Native. He is a well-known artist and when I was looking at his work, Coyote just popped out of my hands and started going on these different adventures and uncovering different aspects of our culture.

The painting The Sisters, tells our story of how Pleiades (a star cluster also called the Seven Sisters) came to be. In the painting, we see Coyote falling back from the sky and holding a magical rope attached to the Seven Sisters. Coyote sneaks up as they go up into the sky, but the Seven Sisters' plan is to cut the rope and leave him to fall back. They do this because Coyote had murdered the Seven Sisters’ husbands, and the consequence of his actions is that he is to be cut off and become the star Aldebaran, which is forever chasing the Pleiades across the heavens.

Historically Coyote often does things that people shouldn’t do and teaches us that there are usually repercussions. So Coyote does very human things, like things we all want to do or not thinking about his actions– but for him, there is always a consequence.

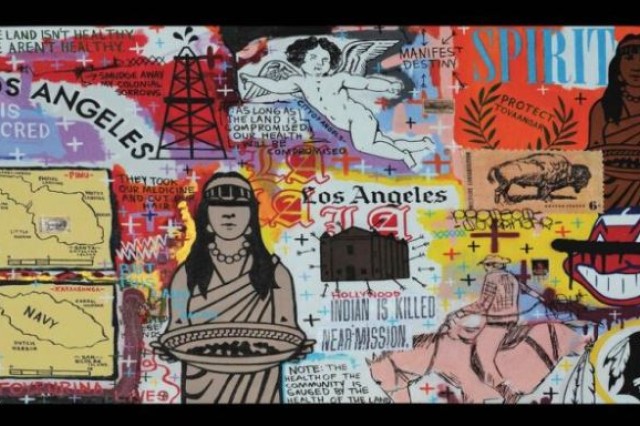

[Tongvaland is] such a wonderful project because of Cara Romero, the Chemehuevi photographer, who got a grant to do something in her lands. She thought, “Hey, how novel, let’s actually include the Tongva people.” So she contacted a couple of us artists, and she asked for a painting of mine. She chose Coyote Drops the Goblet among the various different things I sent her, which made me really happy! It is part of a series of mission pieces that are my reaction to [my people] being obliterated by missions brought here by the other side of my family. Coyote Drops the Goblet is just a rejection of the forced Catholicism on our peoples. Our religions were destroyed because someone else had to put their religion before ours. So here, Coyote would be the one to drop the goblet because he has feelings about genocide and doesn’t seem to really want to accept genocide anymore.

I like the stark contrast between the colors [of my piece] and the sky– it is so visible, so much so that a friend of mine, Malcolm Margolin (author and publisher), said, “Well, that took care of invisibility, didn’t it?” I like it because it’s not imposing, yet it’s not mild either. It’s something coming towards you, it’s something you don’t understand. I love that Cara didn’t give any other explanation other than “Tongvaland.” I think it says plenty. It’s certainly not glorifying the Catholic Church, but there is something happening there. So I’m really stoked that it works so well.

The whole project is just so stunning– Cara’s incredible photographs and River Garza’s art, the entire project as a whole. While I was not surprised, I’m still disappointed that Los Angeles really didn’t pay attention [to the Tongvaland project]. There’s been hardly any print about it from what I've seen– I just haven’t seen it. I know that it’s different and did catch the attention of some people– but it’s hard to bring up the Indigenous people at this point. Because, it’s tricky times, and, you know, we’re supposed to be dead and gone.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

This photograph by Cara Romero titled Mercedes is of Mercedes Dorame, reclining in the sacred waters of Kuruvungna. This billboard was located on La Cienega Blvd.

Cara Romero, Instagram

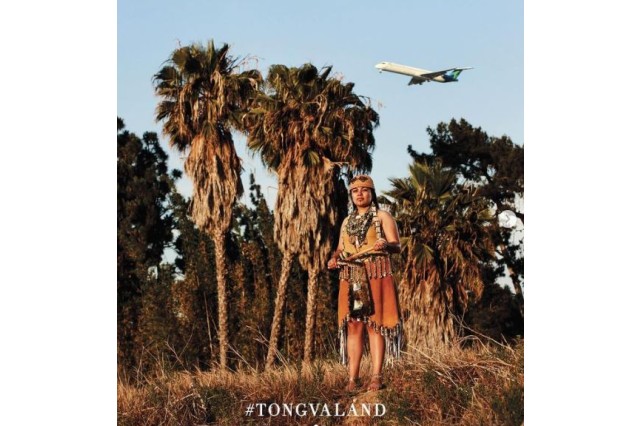

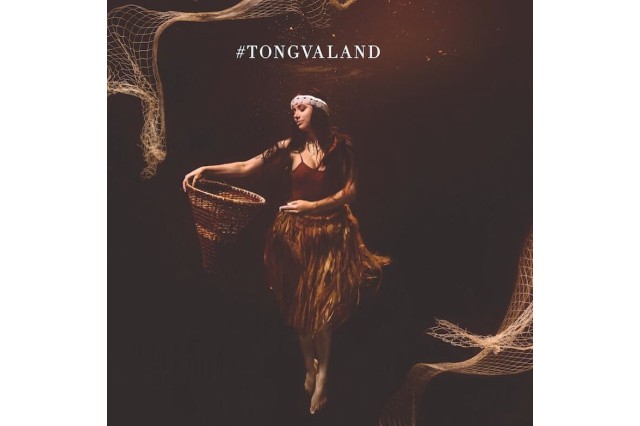

Cara Romero's Miztla at Puvungna features Miztlayolxochitl Aguilera at sunset at Puvungna. The billboard was located on La Brea Avenue and is a testament to the Tongva People’s ongoing care of Los Angeles.

Cara Romero, Instagram

Cara Romero's Weshoyot billboard of Weshoyot Alvitre was displayed at Melrose Ave and Wilton Place.

This artwork from River Garza, titled "What the City Gave Us" is part of the Tongvaland billboard project and shows his "amalgamation of centuries of resistance, forced assimilation, and resettlement and my work reflects those disjointments of memory, tradition, and identity." - River Garza

Weshoyot, Instagram

Weshoyot Alvitre, "Tongvaland." Tongvaland is Los Angeles, which is Tovaangar meaning "the world." This image was mounted on a billboard at two locations on Sunset Blvd and are meant to be a cultural exchange about listening and critically exploring what it means to live on someone else's sacred land.

1 of 1

This photograph by Cara Romero titled Mercedes is of Mercedes Dorame, reclining in the sacred waters of Kuruvungna. This billboard was located on La Cienega Blvd.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Cara Romero's Miztla at Puvungna features Miztlayolxochitl Aguilera at sunset at Puvungna. The billboard was located on La Brea Avenue and is a testament to the Tongva People’s ongoing care of Los Angeles.

Cara Romero, Instagram

Cara Romero's Weshoyot billboard of Weshoyot Alvitre was displayed at Melrose Ave and Wilton Place.

Cara Romero, Instagram

This artwork from River Garza, titled "What the City Gave Us" is part of the Tongvaland billboard project and shows his "amalgamation of centuries of resistance, forced assimilation, and resettlement and my work reflects those disjointments of memory, tradition, and identity." - River Garza

Weshoyot Alvitre, "Tongvaland." Tongvaland is Los Angeles, which is Tovaangar meaning "the world." This image was mounted on a billboard at two locations on Sunset Blvd and are meant to be a cultural exchange about listening and critically exploring what it means to live on someone else's sacred land.

Weshoyot, Instagram

L. 's identity and experiences shine through her artwork, highlighting the underrepresented history of the Tongva. L. also holds leadership positions in another often overlooked group, the Two-Spirit community. Two-Spirit identity is unique to each individual, and as such, it is a hugely diverse term that covers a variety of different cultural groups. We spoke with L. about her thoughts on being Two-Spirit and how she connects with others who identify with this community.

Yeah, exactly that; it does mean whatever people need it to mean. For me, I prefer the word because all the other words remind people of biological sex, the act of sex, your body, what you look like– whose business is any of that? For me, Two-Spirit more appropriately defines that I am more than a sexual being. I’m a sentient and spiritual being. So it holds a lot of weight for me. Though there’s a lot of disagreement about the term, I think it really fits me, and it really fits our community.

There’s one man who had heard our language; he was an elder man who could speak some of the words– and I got to hear him. As a child, I would lay on the ground of a huge burial site where 600 of our tribe were buried, 400 of them women. I laid there for many years, listened to things under the ground, and heard my language. They were the key towards me wanting to talk to real people and to learn this language.

I was doing a lot of private work at first and then connected with a group of California Natives to create the Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival. We held a conference called “Breath of Life, Silent No More” which is for California Natives who need to learn their language. We are losing speakers of the language and it is getting harder and harder to learn because people are getting older and just passing away. We have to move towards archival learning, and I have worked with Indigenous Peoples across the US and Canada to revitalize and reclaim their languages.

I don’t have any linguistic background, although, for about 20 years, I hung out with a linguist over at UC Berkeley and learned a lot. But I also just listened to what our people need. I don’t feel that my needs are that unusual– others also wanted to bury their dead in language, raise their children with language, or pray in language. So yeah, I’m a big language geek.

I work my damnedest to be the person that I want to be. I figure that the only way people can really believe anyone else is through actions. I can talk, talk, and talk, but what have I done for our people lately? I don’t feel that because I did something that was difficult or scary (and it was for our people) that I can rest on that alone, you know? What have I done lately, what have I done for the next seven generations?

Also, people see that I am Two-Spirit– I’ve never hidden, been ashamed, or had guilt over [my identity]. Everyone around me may not have liked it– I’ve been hit, chased, and slugged for it– but within myself, this is who I’m supposed to be so that I can help in certain ways.

For the younger people, I try to be always honest– and I’m way too autistic to really lie, it makes me feel weird. I always try to be honest, I try to listen, I try to be the elder that somebody actually needs, not the elder that I think I should be. So it’s by example.

I’ve been the co-master of ceremonies for the “world’s largest Two-Spirit powwow” in San Francisco. That’s been interesting because I really don’t know anything about powwows but the community is so healed by this powwow. The community just gets larger and larger at the powwow, so people find themselves, their place there. Nobody has to explain anything, and everyone is celebrated. It’s straight families with children, trans people, or questioning people. It doesn’t matter what people’s pronouns are, every pronoun comes away being satisfied, seen, or heard– they have community.

The Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits (BAAITS) runs the powwow [I mentioned] and is a large Two-Spirit organization. It has been around for a long time– I marched with them back when Gay Pride had no barriers, everyone held signs made out of cardboard, and the biggest truck was a pickup truck!

We held a virtual powwow in 2021 because of COVID, and actually, people were really happy. They just missed each other and they missed the strength that they get from that powwow. There’s a fairly large group of Natives throughout the state who understand the Two-Spirit community– we were not shunned but welcomed in the community. Now if we do dopey things, then yeah we’ll be shunned (chuckles), but at least I have been incredibly fortunate to be in this circle of Natives who have never ostracized me for being Two-Spirit. In Native languages, you can find a word for Two-Spirit or you find everybody has a name that we were called. Some cultures and tribes have problems with Two-Spirit, but that is coming from Christianity which came along and took a big bite out of our real lives.

1 of 1

2020 Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit powwow

BAAITS, Instagram

2020 Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit powwow dancer

Norm Sands, BAAITS Instagram

2020 Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit dancer

Norm Sands, BAAITS Instagram

To see more of L. Frank’s work in the Los Angeles community and beyond, you can follow her on Instagram at @toovitum or on Facebook @L Frank Manriquez.

Oftentimes in museums, we see the end product of a work of art, but sometimes the artist goes unseen. This project came about because we wanted to get to know L. Frank, understand her process and perspective, as well as uplift the voices of communities that often feel invisible. Culture is carried through time and L.'s vision of the past, present, and future paints the stories, struggles, and hopes of Indigenous and Two-Spirit communities.

Many people who identify as Two-Spirit do not fit into a gender binary. Among Indigenous people, those who do not fit into a conventional gender category may feel an additional layer of invisibility. Now more than ever it is important to acknowledge our past in order to create a brighter future for those who often go unseen and celebrate those who may have these intersectional identities.

Like all those out there working to share their stories and those of their communities through art, L. Frank’s work is never finished. She has been part of a larger team of Southern California tribal members collaborating with and advising the Museum on an upcoming Channel Islands exhibition to ensure their stewardship and knowledge of that land guides its development. L. Frank has also received a recent grant commission to construct a traditional plank canoe called a ti’aat for the Queer Cultural Center in an upcoming collaboration with associated tribal groups called Eyoomukuuka’ro Kokomaar (We Paddle Together).

Additional contributors: Val Hatcher, Ashley Moody, and Milena Acosta