A Giant Fish Story

An extremely rare adult giant sea bass specimen makes its way to NHM

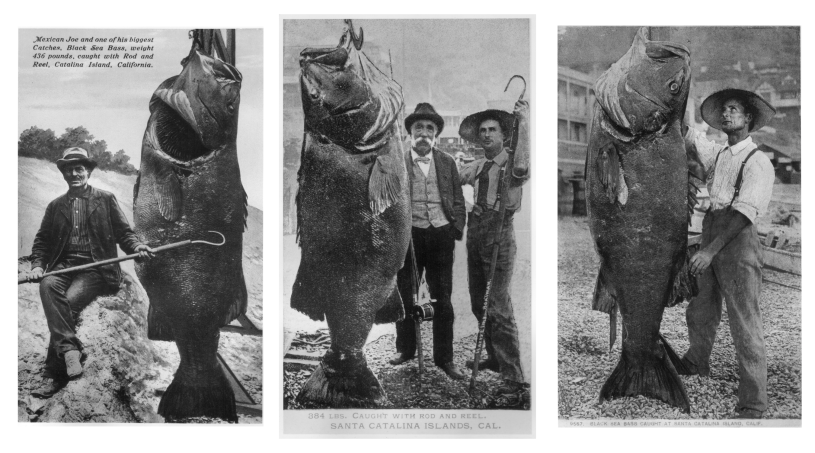

Every item in the Seaver Center for Western History Research's collection of two-dimensional objects tells a story, and some photos, like the giant sea bass photos below, catch the drift of natural history.

Taken at Santa Catalina Island, the photos depict fishermen next to impressive giant sea bass, exhibiting the fish’s immense size. These undated angler photos highlight how common these incredible fish used to be, and how quickly even the biggest animals can disappear. By the 1950s, these once plentiful giants were vanishing, and 20 years later were almost extinct off of California’s coast.

This is why one showing up outside NHM via pickup truck in a kiddie pool full of ice was such a welcome–if challenging–event. “It's not often that someone asks you if you want a five-foot-long giant sea bass for the collection, so you know you're going to take it even though it will be a lot of work to prepare,” says Dr. Bill Ludt, NHM’s Assistant Curator of Ichthyology.

These huge fish have huge appetites, rapidly opening their mouths which creates a vacuum that can hoover up an almost comically long list of prey from the waters around them: octopus, squid rays, guitarfish, skates, sheephead, sargo, small sharks, barred sand bass, kelp bass, blacksmith, ocean whitefish, cephalopods flatfish, and spiny lobster. If it’s big enough to fit in their mouth, giant sea bass probably eat it, which is part of why better understanding them is so important to understanding California’s marine ecology. Giant sea bass play some role in keeping their prey species populations controlled.

“Giant sea bass are one of the largest predators we have along our coast, and are particularly important for rocky reefs and kelp forests where they sit atop the food chain.”

“You don’t want to lose your top predators,” says Ludt. “It throws off the balance of the food web. In fact, due to overfishing, it could already be off balance as it is difficult to study the impact that this species has on community structure when their population levels are already so low.”

The giant sea bass off our coasts aren’t technically bass (they are evolutionary oddballs placed in their own family with only one other closely related species) but they are literal giants. The largest recorded fish tipped the scales at nearly 600 pounds. A report from the early 1900s describes a 700-pound fish. Their large sizes come with long lives (more than 70 years), but earlier, unverified reports describe fish over a hundred years old. Long lives mean sexually maturing later, and the baby giants are tiny enough to be prey for the bevy of animals the adults feed on. The difficulties of studying and conserving them are wrapped up in giant sea bass’ eye-popping stats and their tenuous conservation status.

Conservation laws can make active collection difficult, and researchers wouldn’t want to decrease the already low population by taking a fish from the wild, so any specimen added to museum collections has to be salvaged–meaning somebody gets to the dead fish before other hungry animals do. The result is that while the fish are thankfully better protected, a paucity of preserved specimens makes them more difficult to study for museum researchers.

The sheer size of these creatures makes them challenging to keep and prepare for natural history collections, which generally have a size bias—the bigger specimens are, the harder they are to store. When you’re trying to catalog all life on Earth, storage space becomes a hot commodity.

“Even though we don’t have unlimited space to store a lot of large individuals, it’s really important to have individuals in our collection that represent all stages of life, especially if it’s a rare or protected species that is hard to study in the wild.” – Dr. Bill Ludt

Photo by Tyler Hayden

A juvenile giant sea bass in the Ichthyology Collection. Understanding an animal’s ontogeny, the behavioral and anatomical changes happening from the beginning of its life until maturity, is essential, especially in protected species like the Giant Sea Bass.

Photo by Tyler Hayden

Ichthyology Curator Dr. Bill Ludt holds an older juvenile specimen. Giant sea bass grow drastically over a relatively long period of time–10 to 13 years until fully grown. These immature fish are still large enough to warrant using the largest jar size in the fish collections.

Photo by Tyler Hayden

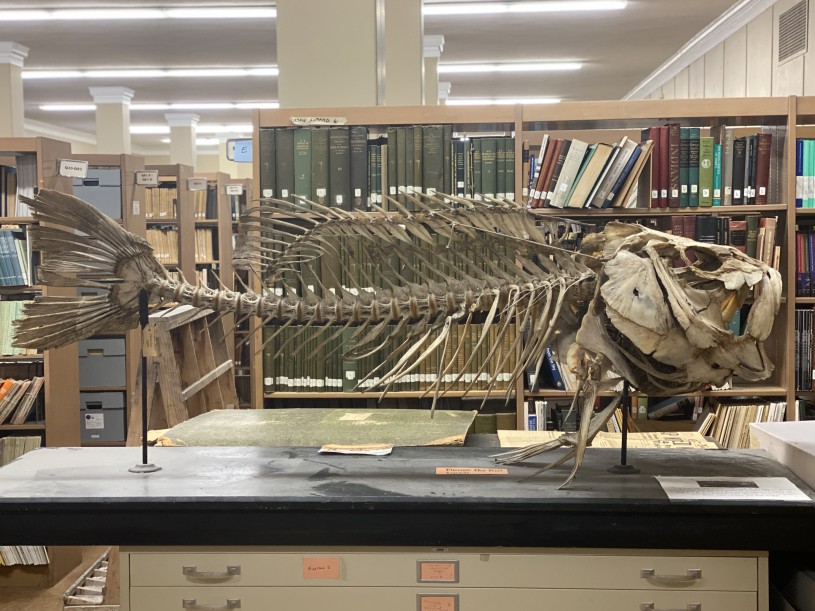

Giant sea bass historically was known to grow over seven feet in length and weigh more than 500 pounds. When prepared, the new specimen will be too large for storage in the compressed shelving where most of the Ichthyology Collection is housed.

1 of 1

A juvenile giant sea bass in the Ichthyology Collection. Understanding an animal’s ontogeny, the behavioral and anatomical changes happening from the beginning of its life until maturity, is essential, especially in protected species like the Giant Sea Bass.

Photo by Tyler Hayden

Ichthyology Curator Dr. Bill Ludt holds an older juvenile specimen. Giant sea bass grow drastically over a relatively long period of time–10 to 13 years until fully grown. These immature fish are still large enough to warrant using the largest jar size in the fish collections.

Photo by Tyler Hayden

Giant sea bass historically was known to grow over seven feet in length and weigh more than 500 pounds. When prepared, the new specimen will be too large for storage in the compressed shelving where most of the Ichthyology Collection is housed.

Photo by Tyler Hayden

Even as this rare specimen comes to the Museum, giant sea bass seem to be making a comeback. A 2015 survey of their breeding grounds off of Santa Catalina–the same island where anglers reeled in their enormous catches in those historic photographs–found the beginnings of a new revival. With animals that take so long to reach reproductive maturity, comebacks are hard to pull off. Enough young giant sea bass need to survive more than a decade before they're ready to breed.

There’s still a long way to go for giant sea bass to recover. “They’re not out of the kelp forest yet,” Ludt says. Specimens like the newly acquired giant sea bass will be essential to helping scientists understand these gentle giants, and guide the recovery of these magnificent fish–and our coastal ecosystems–to safer waters.