The Anglerfish Artist

Dwight Hwang, an expert at the traditional Japanese printing technique called gyotaku, was invited to the museum recently to perform a marriage of art and science

A Pacific footballfish, a type of anglerfish whose typical habitat is between 1,000 and 4,000 feet underwater, was discovered on Newport Beach at the end of May. Soon after, our museum ichthyologists were welcoming the deep-sea creature into our collections.

“It is extremely rare, one of only about 30 adult female specimens of this species [in collections globally], and having one washed up in this condition is extraordinary,” said NHM Assistant Curator of Ichthyology Dr. William Ludt. This is only the fourth species of Himantolophus sagamius now housed at NHM. “I love all fishes, but this one is definitely special. Like anything in biology, what we know about a species depends on how many individuals we have of that species to learn from. We feel very fortunate to add her to the collection!”

This discovery was extra thrilling for Ludt and Ichthyology Collections Manager Dr. Todd Clardy when a celebrated artist offered to make the fish immortal. Dwight Hwang, a well-known local practitioner of the traditional Japanese folk art gyotaku, contacted the museum soon after the local news showed a beachcomber, Ben Estes, had happened upon the glistening fish on the Crystal Cove sand.

Centuries ago before cellphone cameras were go-to recording devices, the art of gyotaku served as a way for fisherman to register trophy catches. A famous 19th century nobleman, Lord Sakai, tasked his calligraphers to document each big fish they lured to the surface, along with its weight, how they caught it, and the time of day. Contemporary artists use the same techniques: ink the surface of the specimen, press the paper down, and reveal elegant portraits of these denizens of the oceans.

Before Hwang and his wife Hazel, who work in tandem, began to print the 15-inch-long rarity, they considered their approach carefully. The pair did a mental inventory of other creatures they’d worked on. There were other deep-sea creatures, such as the dragonfish and lanternfish, which were gelatinous and fragile. They had printed delicate seaweeds that had similar slippery qualities. But this anglerfish also had sharp spines over its body like a prickly pear cactus. Because it was rare and pristine, and the slightest touch and rub could cause skin to peel off, they made sure to gingerly apply the ink and used thin paper. Hwang decided to let the spines pierce the paper and to mend the holes later.

“I’ve worked with sea urchins and spiny lobsters, and having something completely spiny is one thing, but having something that’s partly spiny and partly gelatinous was really difficult. I was trembling and sweating! This is by far the most difficult fish we’ve printed. Hands down.”

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

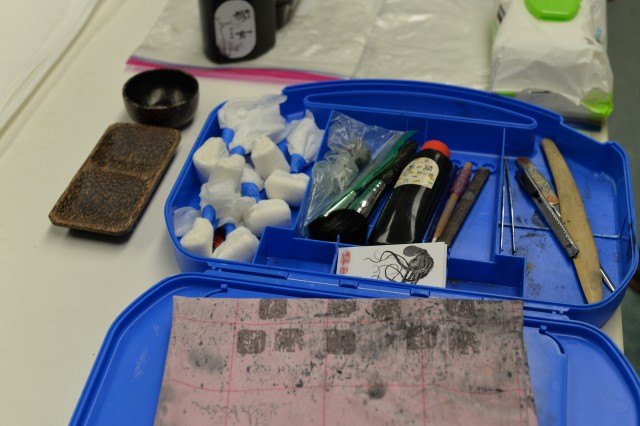

Toolbox for the gyotaku printing

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

Artist Dwight Hwang delicately cleans the surface of the specimen on a table in the museum's Ichthyology lab.

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

Applying the ink to the football-sized specimen while watching out for spikes!

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

Gingerly applying the thin printing paper to the inked fish

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

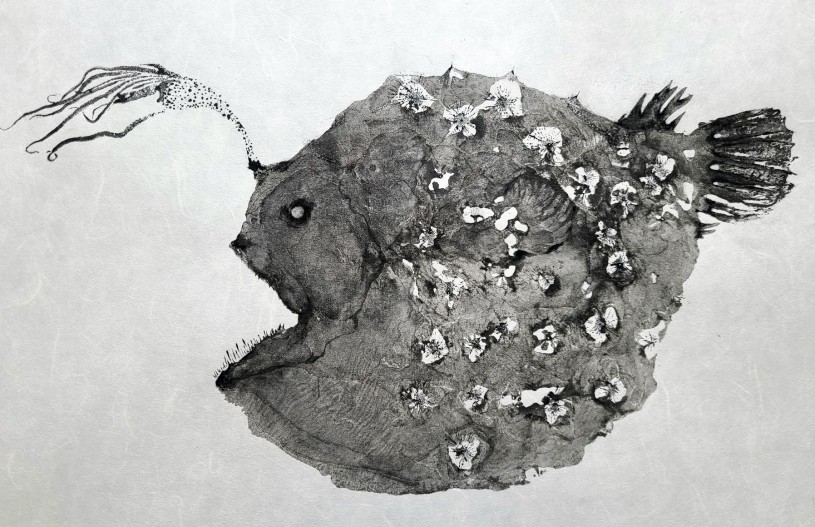

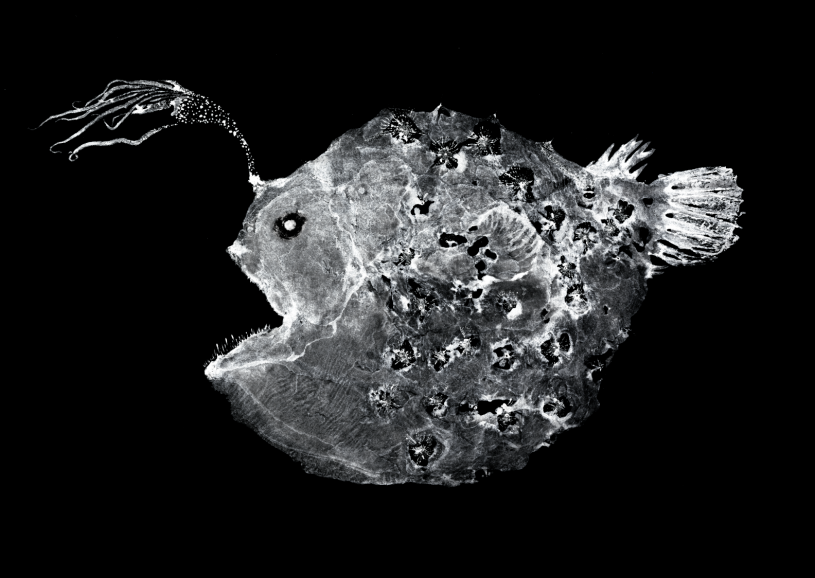

The fleshy long filament that extends in the front of the anglerfish's mouth is bioluminescent and is used to attract prey in the pitch-black habitat where she lives.

1 of 1

Toolbox for the gyotaku printing

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

Artist Dwight Hwang delicately cleans the surface of the specimen on a table in the museum's Ichthyology lab.

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

Applying the ink to the football-sized specimen while watching out for spikes!

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

Gingerly applying the thin printing paper to the inked fish

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

The fleshy long filament that extends in the front of the anglerfish's mouth is bioluminescent and is used to attract prey in the pitch-black habitat where she lives.

Photograph by Brian Bergeron

Prized Catch

Printing the anglerfish's spooky-looking lure (think Disney's Finding Nemo) proved a slightly easier undertaking. The fleshy, long filament that extends in the front of the mouth is bioluminescent and is used to attract prey in the pitch-black habitat where she lives. Ludt explains that the bioluminescence occurs because the esca houses symbiotic bacteria, and that (not the animal) produces the glow that squid and smaller fish are attracted to in the dark depths.

The end result of the day? Two stunning prints. “We knew Dwight would make it phenomenal,” Ludt says. Having scored a touchdown with this footballfish, Hwang is hooked on NHM. The artist is coordinating with our mammalogists and ornithologists to identify other taxidermy animal specimens in the museum’s collection which might also be exquisitely rendered for art and nature unions for eternity.

Watch Dwight Hwang talk about how he created these incredible prints: